This will be the first of probably several dispatches from Czechia. If you read this blog only for Russia-related news, I apologize, and you can skip this one, or even unsubscribe out of disappointment and utter disgust.

Brno hasn’t changed much since my last visit, although it appears the former capital of Moravia is slowly falling victim to degenerate architectural fads.

There was once a lovely square in the historic center of the city called Mendlovo náměstí, where you could mingle with gypsies and purchase knick-knacks and beers from wonderful, filthy kiosks. The square is still here, but they expelled the gypsies and bulldozed the kiosks—or maybe in reverse order. Now it is a sterile, minimalist tragedy desecrated by “modernist” benches that no self-respecting gypsy would sit on.

What is this, Germany?

Meanwhile, Brno’s “Freedom Square” is still as freedom-loving as I remember it: There’s a McDonald’s, a New Yorker sweatshop clothing emporium, and other staples of Western soft power. Admittedly the square does not have enough Ukrainian flags, but I’m sure this can be remedied.

My assumption is that just like everything else in Czechia, Brno is bought and paid for by foreign multinationals. Why the Czechs have agreed to this state of affairs is beyond my comprehension. I suppose they didn’t have a choice. Many of them probably even like it. Personally, I’m a Moravian ultra-nationalist and believe all foreigners—myself included—should be deported from this sacred land. (I think they actually did this after the Second World War, and it’s a bit of a touchy subject.)

But I cannot hate on Brno too much, because it is very dear to my tender heart, and I actually teared up a bit while sitting in a cozy corner of the city (the location is secret because you will ruin it) as I sipped on a glass of Božkov rum.

Božkov rum is actually a perfect illustration of why, as a Moravian ultra-nationalist, I firmly believe Czechia must liberate itself from the Brussels Protectorate. The European Union has 1,000 pages of regulations stipulating what can and cannot be considered rum, and since Božkov did not meet these rigorous standards, the company actually had to rebrand its liquor as “Božkov tuzemák”—which translates to “Božkov domestic”.

Imagine being the nation that blessed humankind with arguably the world’s best potato rum, and then having to betray your proud heritage because the EU is racist against potatoes. (Full disclosure, because I just checked: Božkov is no longer made with potatoes. They changed the formula in the 90s. Still, everyone calls it potato rum.)

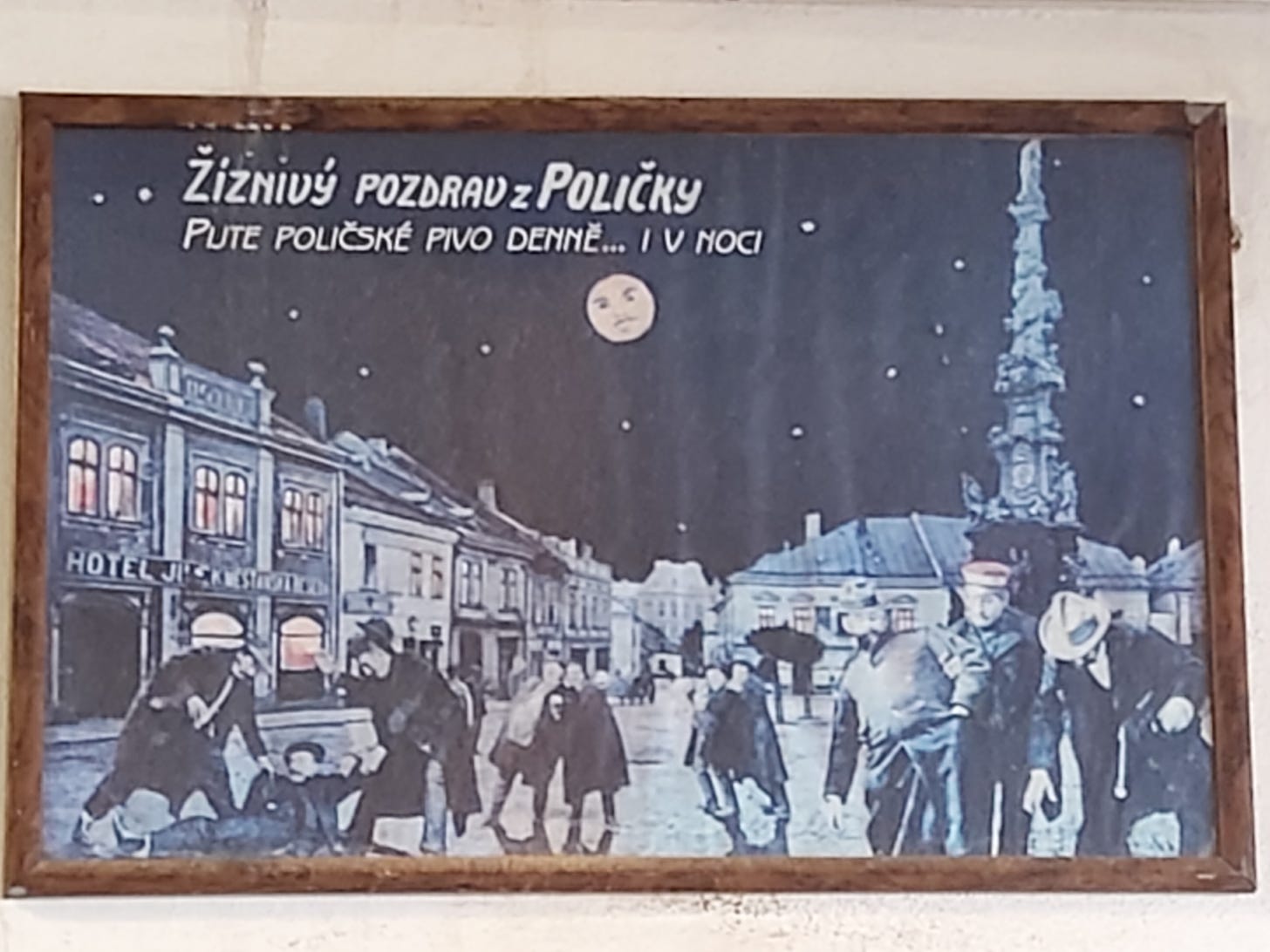

A pilgrimage to Polička

When the ignorant masses think of Czech beer, they often think of Pilsner Urquell, or maybe Budějovický Budvar. God help them if images of Kozel or Gambrinus appear in their noodles.

I will not go so far as to say these are bad beers, but you’re really limiting yourself if these are the Czech beverages you like to drink.

I’m a Polička man, myself. I was first acquainted with this beer after discovering it at a Brno pub called Café Laundry. The original concept of this establishment was that you could sip on something pleasant as you did your laundry. However, I returned to Café Laundry yesterday for research purposes, and the washing machines were gone. I think it was a short-lived gimmick. Also, Brno is famous for its freeloading, deadbeat hippies—complete with dreadlocks—so maybe the washing machines were never necessary.

The reason I prefer Polička to other Czech beers is because it is the best Czech beer, and if you don’t drink it you are a fool.

On Tuesday I hatched a brilliant plan: Why not bypass the dreadlocked middleman, and go straight to the source of this frothy, golden potion? A very dear Czech friend also expressed interest in making a pilgrimage to Polička, and so that’s what we did.

Polička has a lovely central square lined with many well-maintained buildings dating back to a time when architecture wasn’t about building soulless cubes. The town also enjoys notoriety for its well-preserved walls from the 14th century. It’s a very nice place I highly recommend it.

The Pivovar was just a short walk from the town’s walled-in center.

Our plan briefly hit a wall when we arrived at the brewery. The pivovar did not feature a pub or restaurant (which is highly unusual), and private tours needed to be reserved in advance.

After deploying the usual female guile, my companion convinced the brewery’s security guard to call his manager.

“There’s an American who loves Polička [True — Edward], and came all the way from America [False. Typical female trickery — Edward] to visit your brewery,” my Czech friend cooed through the phone.

Eventually the manager relented, but he asked us to return in two hours. We returned to the town square and drank Polička while we waited.

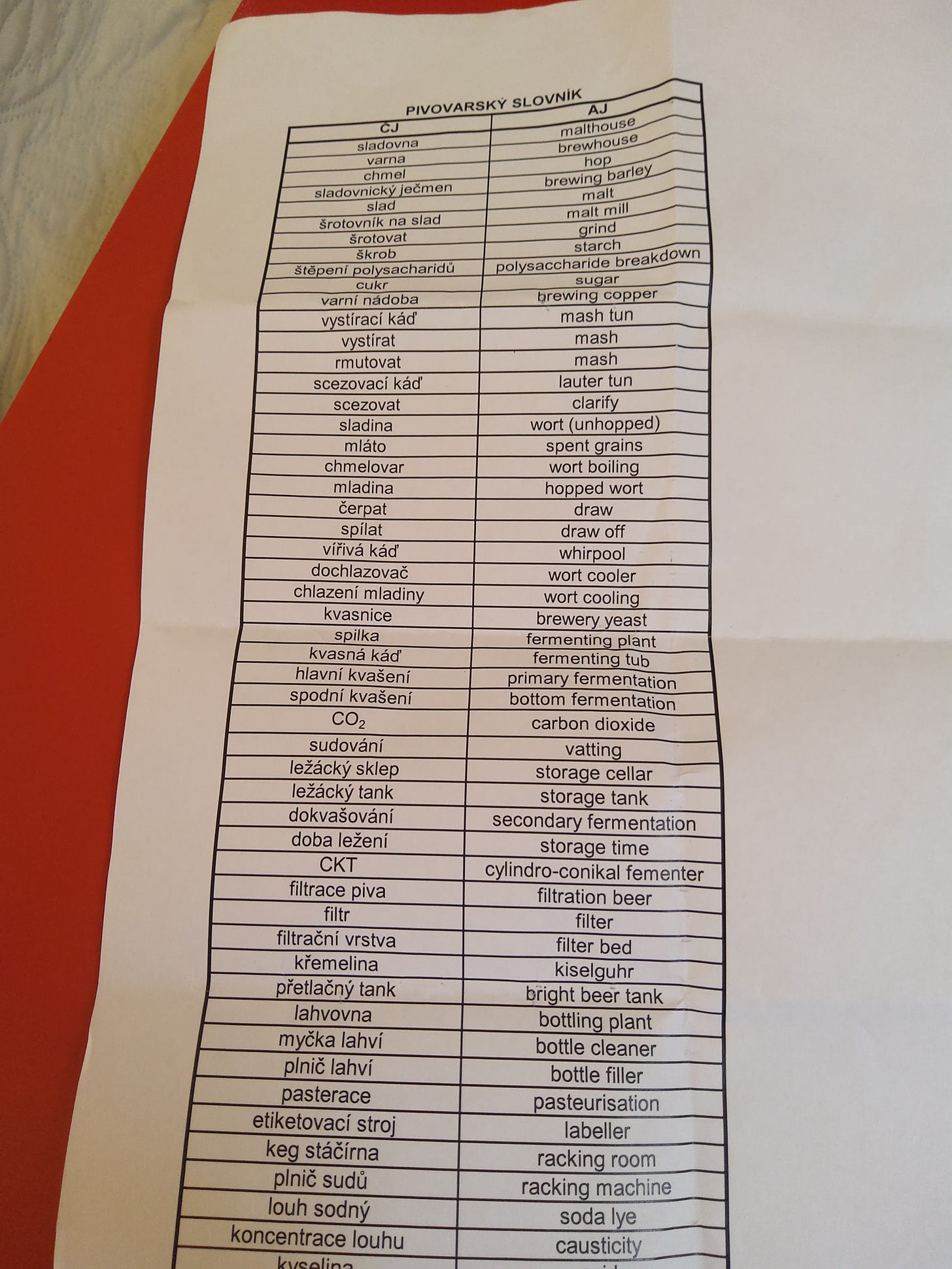

The gentleman who showed us around the brewery gifted me a helpful beer-related vocabular list before starting the tour. Considering I struggle immensely when trying to relay simple concepts in Czech, I’m not sure if I will ever have the opportunity to use the Czech word for “wort cooler”—but you never know.

The brewery was very interesting. It would have been more interesting if I understood more than 5% of what was said, but so it goes.

At the end of the tour we were given a heavenly, cold glass of Polička, which had been delicately squeezed from the brewery’s main udder. It was very likely the best thing I have ever put in my mouth.

After the pilgrimage was complete, we visited a friend who lived in a village 20 minutes from Polička. Together we drank more Polička. Then the aforementioned friend banged on a drum for the local cows. They say it calms them.

The cinematography is my own, and its unmatched quality is further proof of the superiority of Polička beer.

And that was my trip to Polička.

This morning I noticed that all of my fingers had well-trimmed nails, except for one. How this happened I will never know. But when I sought to correct this problem, I realized I had misplaced my nail clippers.

There is a pharmacy next to a popular hookah lounge in Brno, so I popped in to get myself some kind of nail-removing device.

The only thing they had was a “premium nail care” contraption, made in Germany of course. It looks like a very thin lighter, which you then manipulate in some way to reveal a hidden nail-clipping mechanism. It also came with a mini leather pouch. I assume it is made of stainless steel, or diamonds, or maybe ivory taken from endangered baby elephants, because it was 379 koruna—that’s almost $18. Somehow I always find a way to get scammed.

Now I’m on the train to Prague, and I just found my not-premium nail clippers. They were exactly where they were supposed to be, in my bag, in the pocket where I always keep them.

Until next time.

My eyes are welling up seeing Riley's transformation from an average Yankee drinking Bud Light to a fine Eastern European connoisseur downing exquisite rum like a trooper.

To explain our beloved EU having problems with rum:

Some time after year 2000 EU dictated that liquors can only be called whiskey, brandy, or egg liquor etc. – if they are actually made of cereals, wine, or eggs – Slovak spirits’ producers, whose main ingredients were traditionally potatoes and a palette of artificial flavourings, had a problem. But they soon discovered a solution, and so gin became G-38, or G-40, depending on the percentage of alcohol. And traditional Slovak rum, which has never seen a bit of sugar cane, dropped the “r” and became simply “um”

https://www.mabo.sk/rum-tuzemsky-um-40-100-l

In Czech Republic I think the word "tuzemák" is used instead of rum (which is a slang expression meaning "made in our country")

https://www.destilerka.cz/tuzemak-80-1l

In 1997 as I was leaving a job in Slovakia I was moored in Brno for a few days with a bad cold. Back then, women would scoop travelers up at the train station and offer them lodging in their apartments. That sweet babička nursed me until I was up and moving again. I do remember the town square as lovely but it seems especially soulless now due to the lack of trees. Surely EU regulations don't prohibit trees? Or maybe they do now given how pestilent they've become. Na zdravi!