Ukraine: What would victory look like?

A plea for outcome-focused discussions about the war in Ukraine

On Friday, Brian Gerrish of UK Column joined Jesse Zurawell on his TNT radio program to discuss how Russia’s Special Military Operation in Ukraine is reported (both in mainstream and alternative media), and in what ways this coverage might affect our perceptions of this conflict.

You can listen to their chat here.

First, I want to say that I think they both did a great service to the “alternative media ecosystem”. They hold very different views about this war, and their conversation, on the whole, was civil and respectful. I hope similar dialogues will be organized in the future, in an attempt to bounce ideas off each other, and find common ground on this very contentious and divisive topic.

This blog post, which is extremely long (sorry, but there was no other way), is my response to their discussion. Actually, it is an attempt to answer a question that they touched on, but didn’t expand upon, possibly due to time constraints.

Most of their talk focused on casualty figures, and what they may (or may not) tell us about the progression of this war, and who is “winning”. The reason for this is that Jesse, in a Telegram post, criticized UK Column’s coverage of the conflict (which places a lot of emphasis on casualty numbers), and Brian requested an opportunity to respond to this criticism.

To summarize their discussion: Brian believes these figures (which, we must point out, are difficult to independently verify, but can certainly be estimated using various techniques) are of the highest importance, and conclusively show that Ukrainians are being slaughtered for no good reason, constituting a horrific crime perpetrated by Kiev and its Washington/NATO sponsors.

Jesse, on the other hand, questions the relevance of these figures (partly due to how difficult they are to verify), but also because they may not be the best way to gauge who is really “winning”—an argument we will return to shortly.

I would like to briefly address Brian’s perspective about the importance of casualty numbers.

UK Column’s reporting on these figures largely relies on data released by Russia’s Ministry of Defense, which Jesse didn’t like very much. Jesse argued that, just like the “official” figures from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, these numbers can’t be considered objective or impartial.

As someone who follows Russian-language media very closely—especially commentary coming from patriotic voices inside Russia—I would like to point out that many Russians view the “official” casualty figures from Russia’s MOD (Ukrainian casualties, of course—Russia’s MOD rarely speaks of Russian dead/wounded) with extreme skepticism. Actually, these figures are often openly mocked.

For example, in June 2022, Military Review (Russia’s most popular national security news portal, edited by pro-military hardliners who regularly refer to Kiev as a den of Nazis, and do not consider Ukraine to be a legitimate state), published a scathing op-ed, which contained some “constructive criticism” for Lieutenant General Igor Konashenkov, the chief spokesman for Russia’s MOD:

[If we trust the figures given by the Russian MOD], it turns out that all Ukrainian heavy equipment has been destroyed (even “with a margin”), and the Armed Forces of Ukraine cannot continue hostilities. In reality, however, we see a completely different picture. […]

We do not know what methods the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation uses when counting the destroyed military equipment and combat aircraft of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. However, these methods raise serious questions regarding the reliability of the announced figures. If the numbers of destroyed [Ukrainian] weapons, given by General Konashenkov, were true, then the Ukrainian army should no longer exist.

In general, there are certain questions about [the Russian MOD’s] information policy.

In short: If you take the statements from Russia’s MOD at face value, it appears Ukraine’s military no longer exists. Well, it existed in June 2022, and it certainly exists today.

Jesse mentioned Military Review, and its views, to Brian. I was surprised by Brian’s response, though. Brian suggested—in an unhelpfully vague way—that Military Review might not be reliable, because we don’t have a clear understanding of who (or I guess “what”) is behind it.

Since I consider this outlet to be an invaluable “window” into how patriotic, pro-SMO Russians view this conflict (after all, if you are deeply invested in the destruction of “Nazi Ukraine”, what possible reason would you have to unfairly disparage or discredit the Russian MOD?), I would greatly appreciate if Brian could reveal to me why he might think Military Review is untrustworthy. I cite this outlet on a semi-regular basis, so if he has information that raises legitimate questions about its “true motives” it would help me a lot.

But actually, the accuracy of the Russian MOD’s casualty figures is not my main concern with using these figures to assess how this conflict is playing out.

My main objection to focusing on casualties is that the number of dead or wounded Ukrainians does not provide a clear picture of whether or not Russia is achieving its stated goals in Ukraine.

This is a point that Sergey Glazyev (who is held in very high esteem in Western alt media circles; Pepe Escobar referred to him as the “Russian geoeconomics Tzar”) made, in a rather eloquent way, in January:

The uncertainty of the coming year lies in the lack of strategy from Russia.

Our leadership tried to seize the strategic initiative from the United States by accepting the LDNR, Zaporozhye and Kherson regions as part of the Russian Federation.

But it is impossible to keep [the initiative] without a clear ultimate goal, a clear ideology, and a full-scale mobilization of resources to win this hybrid war with the Collective West.

The prolongation of the Special Military Operation (SMO) fully fits into the strategy of Washington and London, who are escalating the war with each passing day at the expense of the EU.

Their puppets in the EU leadership demand a war to defeat Russia, regardless of its negative consequences for Europe. The calculation of the American-British secret services to wear down the forces of the Russian people in this fratricidal conflict is confirmed with each passing day of its continuation.

Worse, the reports of our Ministry of Defense have been reduced to stating the number of Ukrainian servicemen killed, which allows the enemy to interpret the goals of the SMO precisely in this indicator.

The transition to a long trench war, like the infamous Verdun meat grinder, which claimed the lives of a million French and Germans in the First World War, is fraught with disaster for the Russian world.

When high-ranking generals of the Ministry of Defense report on television the daily results of hostilities, citing the number of Ukrainians killed, millions of Russian citizens with relatives in Ukraine clutch at their hearts.

The lack of a clear strategy and ideology for the whole of society, in this world hybrid war, allows the enemy to interpret the SMO in the Russophobic terms he needs, plunging the Russian public consciousness into a depressive state, and undermining trust in the authorities.

The prolongation of hostilities until next year creates the prerequisites for a political crisis in Russia.

Yes, those are the words of Sergey Glazyev.

But Glazyev has a larger, more profound observation: Preoccupation with the number of dead Ukrainians obfuscates a far more vital metric: Namely, progress towards achieving outcomes that are beneficial to both Russians and Ukrainians.

And it is this subject—assessing Russia’s progress towards achieving its stated goals in Ukraine—that I would like to focus on for the remainder of this blog post.

What are Russia’s objectives in Ukraine?

First, let’s refamiliarize ourselves with Putin’s February 24 address. I am going to quote directly from it, highlighting what I believe are the justifications that Russia’s president gave for launching the Special Military Operation:

“Any further expansion of the North Atlantic alliance’s infrastructure or the ongoing efforts to gain a military foothold of the Ukrainian territory are unacceptable for us. Of course, the question is not about NATO itself. It merely serves as a tool of US foreign policy. The problem is that in territories adjacent to Russia, which I have to note is our historical land, a hostile ‘anti-Russia’ is taking shape. Fully controlled from the outside, it is doing everything to attract NATO armed forces and obtain cutting-edge weapons.”

“For the United States and its allies, it is a policy of containing Russia, with obvious geopolitical dividends. For our country, it is a matter of life and death, a matter of our historical future as a nation. This is not an exaggeration; this is a fact. It is not only a very real threat to our interests but to the very existence of our state and to its sovereignty. It is the red line which we have spoken about on numerous occasions. They have crossed it.”

“The purpose of this operation is to protect people who, for eight years now, have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kiev regime. To this end, we will seek to demilitarize and denazify Ukraine, as well as bring to trial those who perpetrated numerous bloody crimes against civilians, including against citizens of the Russian Federation.”

Now let’s distill these statements into concise objectives:

To prevent Ukraine from becoming a hostile “anti-Russia” state, armed with NATO weaponry.

To reverse or halt the policy of “containment” carried out by Washington, which poses an existential threat to Russia’s sovereignty and “historical future as a nation.”

To protect the people of Donbass.

To “demilitarize and denazify” Ukraine, and bring to justice those accused of carrying out crimes against civilians.

Which of these objectives have been accomplished, after almost one-and-a-half years of hostilities?

Because there are four parts to this answer, some aspects are open to interpretation, while others have only one logical conclusion. Obviously, I fully recognize that the current status of these objectives are subject to change.

I will provide my own answer, based on my understanding of the current situation.

To prevent Ukraine from becoming a hostile “anti-Russia” state, armed with NATO weaponry

Ukraine has never had more NATO weapons than it does now. It doesn’t matter how many Leopards have been vaporized, the fact that Ukraine is swimming in NATO weapons is not up for debate.

Pre-February 24, the Ukrainian military had received training from NATO, as well as arms, but nothing compared to what is has now. Of course, maybe the Collective West will eventually pull the plug, but for now, the weapons (including advanced systems, tanks, and hardware) are flowing into Ukraine at a rather alarming rate.

Gauging progress towards preventing the formation of a permanent, Washington/NATO-backed “anti-Russia” in Ukraine is not so straightforward, as there’s no way to definitively answer if this is achievable—time will tell. But as things currently stand, it’s difficult to envision how this objective will be accomplished. If anything, the creation of an “anti-Russia” is rapidly accelerating in areas under Ukrainian control (which is still the vast majority of the country).

I firmly believe an impartial assessment of the current situation would result in this conclusion, for a host of reasons.

First, Ukraine has never been more hostile to Russia than it is today. The milquetoast “pro-Russia” elements in the country (in the form of opposition parties, public figures and activists) that existed pre-February 24 have been outlawed by Kiev. Any Ukrainian who is suspected of even timid support for Moscow risks serious retribution, either at the hands of the SBU, or from angry mobs.

In fact, many pro-Russia Ukrainians have expressed bafflement, frustration, and outright anger at how the SMO has been executed.

Strana.ua, which was targeted by Kiev for its “pro-Russia” editorial line, published an eye-opening article about this phenomenon in March 2022, which I encourage you to read (the link is to an English translation).

These misgivings were further exacerbated by the Russian military’s “regroupings” around Kharkov and Kherson, which essentially threw locals who “collaborated” with Russia under the bus. Some were evacuated, others got a knock on the door from the SBU. Either way, it’s quite understandable why Ukrainians would be hesitant to welcome Russia as a liberator if there’s no guarantee that the Russian military will stay. To make matters worse, Moscow has been very tight-lipped about what its true intentions are in Ukraine. (In fact, Putin declared in his February 24 address that “it is not our plan to occupy the Ukrainian territory.”)

The incorporation of several Ukrainian regions into the Russian Federation helped clarify these nebulous, mixed signals, but the “regroupings”, and the fact that the Ukrainian military is still entrenched in all of Russia’s new territories (including Lugansk, although the AFU only control a sliver of this region), has undoubtedly created a rather precarious situation for locals—and I’m being charitable with my word choice.

Secondly—this point ties directly into the first—the war has been a boon for Ukrainian nationalists, and has been used by Kiev as the genesis story for a distinct Ukrainian state, separate and openly hostile to its shared past with Russia and the Soviet Union. The birth of this new Ukraine can be traced back to Maidan (further back than that, actually), but a war with Russia serves as the ultimate nation-forming moment for Ukraine. From the perspective of Ukrainians who disown their common history with Russia, there cannot be anything more visceral.

The evidence for Ukraine’s increasing intolerance for Russia, on a civilizational level, is overwhelming, and would require a separate blog post to detail in full. But I would point to the active campaign of “de-Russification” and “de-Communization”, which has led to all sorts of troubling activities, including the banning of Russian literature, and the destruction of Soviet and Russian monuments and statues. Of course, all of this began in earnest after Maidan—but the SMO did not stop it. On the contrary, it’s become much, much worse.

As the Strana.ua article pointed out, before the start of the SMO, pro-Russia Ukrainians were hoping for “a change in the external and internal political course of Ukraine, the establishment of good neighborly relations with the Russian Federation. That is, essentially, a return to the model Ukraine had in 2013. Putin’s attack, in the eyes of ‘pro-Russian’ Ukrainians, leads the country in the opposite direction—to a sharp increase in the nationalist vector.”

What are realistic, achievable scenarios that could stop and reverse everything listed above?

Not an easy question to answer, because people have vastly different views about what is actually happening on the ground in Ukraine. But actually, the military situation is only part of the equation, because preventing the formation of an “anti-Russia” cannot be achieved militarily, and I cannot italicize that enough.

Nonetheless, let’s begin with two main military scenarios that might help Russia get closer to achieving this objective.

The first scenario involves the complete exhaustion of the Ukrainian military—it collapses, or loses backing from Washington/NATO, essentially neutering it as an effective fighting force. In this scenario, probably Ukraine’s best hope would be to take a permanent defensive stance to prevent Russia from gobbling up more territory, but likely it would mean Ukraine would lose its footholds in the Donbass, Kherson, and Zaporozhye.

My assumption is that this scenario would force Kiev to the negotiating table, and Moscow would be able to dictate the terms. Undoubtedly, these terms would include Ukraine’s neutral status, as well as the reversal of various “anti-Russia” policies.

The problem, however, is that none of this would actually make Ukraine a neighborly state, because neutrality and friendship cannot be decreed via treaty. Even if Ukraine is neutral on paper, that in no way means Ukrainians will hold warm feelings for Moscow. And there’s not a lot Moscow can do about that. There will be bitterness and resentment, and I guarantee Ukrainian nationalism will continue to lurk under official pronouncements of neutrality. This will inevitably lead to difficulties down the road.

On the plus side for Moscow, this scenario would very likely end the bloodshed in Donbass, as well as in the other regions incorporated into Russia, which would fulfill several of Putin’s stated objectives. Serious problems would persist—and would likely lead to conflicts down the road—but it would still be a partial victory for Russia.

The second military scenario is far more extreme. In this hypothetical scenario, the Russian military would find a way to reach Ukraine’s western border, and Moscow would essentially absorb the entire country.

Alexander Dugin recently advocated for this plan of action in an article calling for “preparation for total war to the end”:

What we require now is not a ‘cunning strategy’ but a rational and carefully calibrated plan for victory. Every necessary action for its execution, even those measures that might be ‘unpopular’, should be enacted as swiftly as possible. In the context of modern warfare, speed often dictates the outcome. We cannot afford to be swayed by anyone or anything at this juncture. It is definitely not a time to be preoccupied with elections or popularity ratings.

Here is our situation: a truce appears highly improbable, while the likelihood of an all-out war seems almost inevitable.

You will find similar arguments put forward by Russia’s “turbo-patriots” (most notably Igor Strelkov and his Club of Angry Patriots), as well as various Western alternative media pundits.

Let’s assume such a scenario is militarily feasible, and that Russia’s armed forces push all the way to Lvov.

Putting aside the inevitable mass carnage and ghastly destruction that would be required to make this happen—what would come next?

There would likely be insurgencies and a steady stream of terrorist attacks (probably NATO-backed … have you ever heard of Operation Gladio? Fun times). Would Ukraine become the frontline of a “shadow war”, as Russia implemented various security measures (martial law, “red level terror alerts”, etc.) to try to restore order and stability? Is it unreasonable to presume that these policies would lead to tensions between Ukrainians and the Russian military? Undoubtedly, efforts would be made to stamp out Ukrainian nationalism, and “anti-Russia” activism, but would these policies ultimately backfire?

In this scenario (“total war”), would we see brotherly reconciliation between Russia and Ukraine, or would it create a hornet’s nest of “anti-Russia” sentiment? For Moscow, Ukraine would be “liberated”, but for Washington and NATO, it would become an “occupied” nation, and serve as a breeding ground for arms smugglers, sleeper cells, saboteurs, assassins, etc. Whether you want to admit it or not, probably a nontrivial number of Ukrainians would welcome these undesirables, and might even collaborate with them.

And let’s not forget that the Republic of Ukraine, Russia’s new federal subject, would be surrounded by… NATO. This would also lead to unpleasantness—and would create the conditions for new geopolitical standoffs related to the provocative placement of long-range missile systems, and so forth.

Basically, the “total war” scenario would very likely create years of ceaseless bloodshed and internal unrest, and would probably only galvanize NATO’s attempts to annoy and destabilize Russia, resulting in a very large (and potentially unmanageable) headache for Moscow.

Now let’s briefly examine the less violent paths to preventing the formation of an “anti-Russia” in Ukraine. Again, there are two main ones.

The first scenario is colloquially known as the “I really hope the other side will collapse into its footprint like WTC 7” plan.

This scenario operates from the premise that Ukraine and/or Russia are under serious internal strain—that the proverbial wheels are coming off, economically, socio-politically, etc. etc.—and the conflict will come to an abrupt end after one side is adequately demoralized and destabilized.

Brian made this argument during his conversation with Jesse. He pointed to several socioeconomic indicators that supported the view that Ukraine was “losing”.

I don’t know how anyone could deny that Ukraine’s economy and war effort is basically entirely reliant on Western charity. Well, it’s not really “charity”, because whatever happens, Raytheon and BlackRock will be handsomely rewarded. They always are.

In fact, Kiev’s near-total dependence on Western handouts seems to be an obvious and highly exploitable weak point for Ukraine’s war effort—so why isn’t Moscow taking full advantage of this vulnerability, by severing all energy and resource deliveries to the Collective West? I mean, c’mon, Moscow is paying Kiev to transit Russian gas THROUGH Ukraine. Is this okay? A conversation for another time.

On the economic front, Ukraine is extremely vulnerable—because it is entirely at the mercy of the West.

But this dependency is double-edged: On the one hand, Kiev must rely on the Collective West for its survival.

On the other hand, international banking cartels, and multifarious and highly repulsive corporations, are fervidly eyeing Ukraine as they rub their grubby hands together—in some cases, these sustainable vehicles of profit-extraction have already invested large sums into Ukraine’s “future”. Logically, we must conclude that Western corporations and investment firms will do everything in their power to prevent Russia from robbing them of their various scams and schemes (sorry, “economic development projects”) in Ukraine.

Anyway, to me this suggests Ukraine’s status as a space lizard client state might actually be its “saving grace”, because I doubt Monsanto, BlackRock, Goldman Sachs (etc.) are going to surrender their “investments” without a fight. Or am I missing something?

It should also be pointed out that the “don’t worry, the other side will collapse” theory is also applicable to Russia—although I would just like to stress that I am in no way suggesting it is the most likely outcome. But it’s a possibility that can’t be discounted.

Actually, Strelkov has repeatedly warned about a potential “1917 scenario” taking shape in Russia. What he means by this is that incompetence and feuding among Russia’s upper-management could have catastrophic consequences for Russia’s war effort, and this would inevitably plunge the country into a deep political crisis.

I don’t think it’s necessary to explain why Strelkov thinks this is possible. If you think such a scenario is absolutely impossible, I am envious of your confidence.

Anyway, my point is not that we should prepare ourselves for the inevitable outbreak of (another) Russian Civil War. Rather, I just wanted to point out that there are a number of authoritative, patriotic voices inside Russia who believe the possibility of a “collapse” scenario is not exclusive to Ukraine. Just something to keep in mind.

Returning to how this scenario could help prevent the creation of an “anti-Russia” in Ukraine: Although it would be extremely painful for ordinary Ukrainians (economic devastation can often be just as destructive as bombs and munitions), it might be the least bad option, if we can assume it would lead to a cessation of hostilities, and the removal of the current government in Kiev. It would certainly be preferable to “total war”, for a variety of reasons I needn’t explain.

Of course, the resentment and anger felt by Ukrainians would not dissipate overnight, and many of the problems that I’ve already highlighted—specifically, that you can’t “force” neutrality, even if it’s written on a fancy piece of stamped paper—would still hold true.

(By the way: in a scenario where Ukraine “collapses”, either on the battlefield, or economically, there will undoubtedly be a portion of the population that will blame Zelensky and his cohorts. However, I think it would be very naïve to believe that people in central and western Ukraine would view Moscow as blameless. And what these people think matters a lot, since at the end of the day, the SMO’s success hinges on winning hearts and minds, not “slaughtering” conscripts.)

The second “less violent” scenario that could potentially lead to a neutral Ukraine is a negotiated settlement to the conflict.

I don’t really want to spend too much time hashing out what this hypothetical settlement would entail, but basically, the end result would be everything we’ve already discussed, without the scorched-earth total war, or economic collapse.

Again, the most likely outcome would be Ukraine declaring “official” neutrality, but hopes for brotherly, or at least cooperative, relations between Moscow and Kiev would probably be dashed forever. Or at least for a very long time.

My guess though is that any successful settlement would require serious compromises from both sides, and neither Moscow nor Kiev would be spared a bit of egg-on-the-face. Still, it’s probably the most humane way to end this conflict.

Admittedly, there’s a decent chance that a negotiated settlement would simply be an exercise in irresponsible can-kicking, leading to a resumption in hostilities a few years down the road. (Sigh.)

To summarize, if we look from 30,000 feet at the events unfolding, the prospects of preventing the formation of a permanent “anti-Russia” in Ukraine, backed by NATO weaponry, do not look particularly promising. Hostilities will end eventually, but even a “successful” Russian military campaign in Ukraine will not “win” the hearts and minds of Ukrainians. That task cannot be achieved through bullets and artillery shells.

Objective status: Incomplete. The situation is arguably worse than it was pre-February 24, and it’s unclear how things will get better.

To reverse or halt the policy of “containment” carried out by Washington, which poses an existential threat to Russia’s sovereignty and “historical future as a nation”

The SMO has reenergized NATO—a reprehensible, extortionist arms racket that has spent the last 30 years flattening defenseless nations, because it needs an excuse to exist. Well, now this “defensive alliance” finally has a worthy nemesis, and I’m not sure why people think Washington and its NATO client states would be upset about this. Frankly, I think they are overjoyed.

You can argue NATO is getting cold feet, or that certain members of the alliance have expressed reservations about taking on Russia (Hungary would be a good example), but the fact remains that this rotten club of warmongers has grown in size: Finland, which shares a strategically sensitive border with Russia, recently joined NATO’s ranks, and there’s a decent chance Sweden will as well. There is even a possibility that Ukraine will join NATO, or at the very least, increase cooperation with the alliance (almost redundant at this point). My sincere hope is that this will not happen, because I think it could lead to very terrible things.

I would like to highlight a rather unpleasant reality, which also undermines the notion that this conflict has rebuffed NATO’s deranged fantasy of encircling Russia.

Returning to Putin’s fiery speech on February 24, the Russian leader stated:

I would now like to say something very important for those who may be tempted to interfere in these developments from the outside. No matter who tries to stand in our way or all the more so create threats for our country and our people, they must know that Russia will respond immediately, and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history. No matter how the events unfold, we are ready. All the necessary decisions in this regard have been taken. I hope that my words will be heard.

Well, his words were heard—and promptly ignored. And Moscow did very little (to be honest, nothing) to punish this insolence (despite promises that “necessary decisions” had already been taken, and that Moscow would “respond immediately”, resulting in historic “consequences”).

The painful truth is that from the first hours of this conflict, Moscow has drawn line after line in the sand—and Washington and NATO have crossed all of them, with no meaningful repercussions.

Actually, Washington’s chutzpah is perfectly understandable, considering that Moscow is even unwilling to utilize its critical role in the global economy to bring a swift end to the conflict.

There are numerous examples we can point to, the most conspicuous being the (largely) uninterrupted transit of Russian gas across Ukraine, as well as Russia’s continued willingness to sell enriched uranium to the United States.

There are also a number of economic accords that Moscow has agreed to, which are not being honored by Kiev (Washington). The “grain deal”, for example, which was supposed to create a humanitarian corridor so that Ukrainian and Russian grain exports would be provided safe passage.

Ukrainian exports have continued unmolested (and, according to reports, are primarily going to Europe), but the deal has no “advantages” for Moscow, as Russian Deputy Prime Minister Victoria Abramchenko told TASS on June 16:

[T]he unhindered export of Ukrainian agricultural products through the ports of Ukraine, it is being fully implemented. As for the second part [of the deal]—the connection of Rosselkhozbank to SWIFT, the removal of all restrictions on logistics, insurance of Russian cargo—none of these conditions have been met.

You can argue that this shows Moscow is acting in good-faith, as opposed to its “trusted Western partners”, but if we return to Putin’s stern warning on February 24, it actually doesn’t make a lot of sense. Where are the “historic consequences” for “those who may be tempted to interfere in these developments from the outside”? The grain deal?

There is another related point that I want to underscore before moving on.

Many have argued that Moscow’s reluctance to cut economic activity with the West shows pragmatism, as well as Russia’s belief that Washington’s vassals will come to their senses, and break ranks with NATO’s destructive posturing and machinations.

I don’t find this argument very convincing, mostly because if Moscow’s primary objective was to prevent the needless slaughter of Russians (and Ukrainians), severing economic ties with hostile actors who are actively supporting this slaughter would be a very logical first step before launching into a military conflict.

There’s also a bit of collective, in-group amnesia on this topic.

On December 21, 2021, the well-respected Russia-watcher Patrick Armstrong published a detailed list of what Moscow might mean when it warned of “military or military-technical” measures, as part of an ultimatum issued to Washington.

His article contained a section on economic measures, which included:

— Moscow could break all contracts with countries that sanction Russia on the grounds that a state of hostility exists. That is, all oil and gas deliveries stop immediately.

— Moscow could announce that no more gas will be shipped to or through Ukraine on the grounds that a state of hostility exists

Sending tank columns towards Kiev was not included in his extensive list of possible actions. To Armstrong’s credit, he acknowledged that Moscow could take measures that would surprise everyone—and he was right.

Anyway, his very reasonable article went viral, and many hailed it as highly insightful.

Oddly, the fact that Russia did send tanks barreling towards Kiev, but didn’t cut off gas shipments through Ukraine, has not received the attention I think it deserves. That’s just my opinion, though.

Let’s be honest with ourselves: This is not how you deter an openly hostile threat to your “historical future as a nation”, and if you’ve already decided to take military action to deter this threat, it’s completely nonsensical.

So, with things the way they are right now, I don’t see how you can argue that the SMO has dissuaded NATO from trying to squeeze Russia. In fact, the squeezing has become more brazen, and more dangerous.

I am open to the argument that the SMO has helped Russia reassert its sovereignty by karate-chopping (some) ties with the Collective West, and forcing Moscow to seek out more amiable and cooperative economic partners, but there’s a lot of nuances to this geopolitical pivot. Still, it’s an argument, and I think it’s a valid one.

But, alas, there is still a great deal of work left to be done to declare this objective complete.

Objective status: Incomplete, and the situation is arguably worse (maybe with some caveats) than it was pre-February 24.

To protect the people of Donbass

I won’t spend too much time on this one, because I consider it clear-cut and unambiguous.

The situation in Donbass has never been more violent, destructive, and tragic. The shelling of civilian targets has increased tenfold compared to pre-February 24. The Ukrainian military remains firmly entrenched in large sections of Donetsk (and, as I mentioned earlier, continues to have a small but annoying foothold in Lugansk).

Taking Mariupol was an important and significant step towards liberating Donbass, but it came at a very high cost, and it almost seemed premature when Donetsk was being shelled on a daily basis.

Of course, the situation could change—as I’ve pointed out repeatedly—but for now, I don’t foresee Donbass being cleared of Ukrainian troops even in the medium-term. Incredibly, a significant portion of Ukrainian positions in Donbass haven’t been pushed back an inch since the start of the SMO.

The “protection of the people of Donbass” was the most concrete, tangible military objective—an objective that could actually be achieved through military means alone.

It has not been achieved, and it’s unclear when it will be achieved.

Objective status: Incomplete, and the current situation in much of Donbass is regrettable and tragic.

To “demilitarize and denazify” Ukraine, and bring to justice those accused of carrying out crimes against civilians

This objective is largely a mixture of the previous three stated goals, but I will briefly address efforts to “denazify” Ukraine.

First of all, what does this mean?

Depends on who you ask, but several definitions were offered in the early days of the conflict.

Konstantin Dolgov, Deputy Chairman of the Federation Council Committee on Economic Policy, said on March 4, 2022, that “denazification” involved reeducating Ukrainians:

According to him, denazification is not only not only the liberation from symbols or the prohibition of symbols.

“The bulk of the population [should] understand that Bandera is a Nazi criminal, and others like him too. When this understanding comes, then the process of denazification will be basically completed,” Dolgov said.

A day later, Putin seemed to advocate for a more targeted approach:

“So what is denazification. Here I was talking with my Western colleagues: what is it, you also have radicals. Yes, we have. But we don't have radicals in the government. And everyone admits that there [in Ukraine] is,” Putin said.

He noted that in Russia there are also “some idiots who run around with a swastika somewhere,” but they don’t walk around the capitals with torches, as in Germany in the 1930s, but this happens in Ukraine.

Let’s start with Dolgov’s definition. If Ukrainians need to be reeducated, how does Moscow intend to accomplish this? As I see it, the only way would be to conquer Ukraine, take control of its education system, and then reissue textbooks to Ukrainian schools.

Another possibility is that a negotiated settlement would include clauses prohibiting Kiev from glorifying Bandera, etc. That’s within the realm of possibility, but how this agreement would be put into practice is an open question. It seems like wishful thinking, when you consider how messy and difficult it would be to enforce this policy.

Putin’s definition makes a lot of sense, but what has Russia done in the last 1.5 years to make this happen? None of the Ukrainian oligarchs or political puppets responsible for Ukraine’s “Nazism” have been brought to justice—correct me if I’m wrong.

As I observed in a blog post in July 2022:

It would have been cool if a glider full of heavily armed Spetsnaz landed on Igor Kolomoisky’s roof as part of a dashing operation to handcuff Ukraine’s most prominent scumbags. RT could have livestreamed it, too.

Imagine footage of Igor squealing like an obese piglet as gigga-elite Russian soldiers put a canvass bag over his head (filled with spiders, of course) and frog-march him out of his lavish oligarch-condo in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.

Still hasn’t happened, and I don’t see any indicators to give me hope that it will happen. That’s a pity.

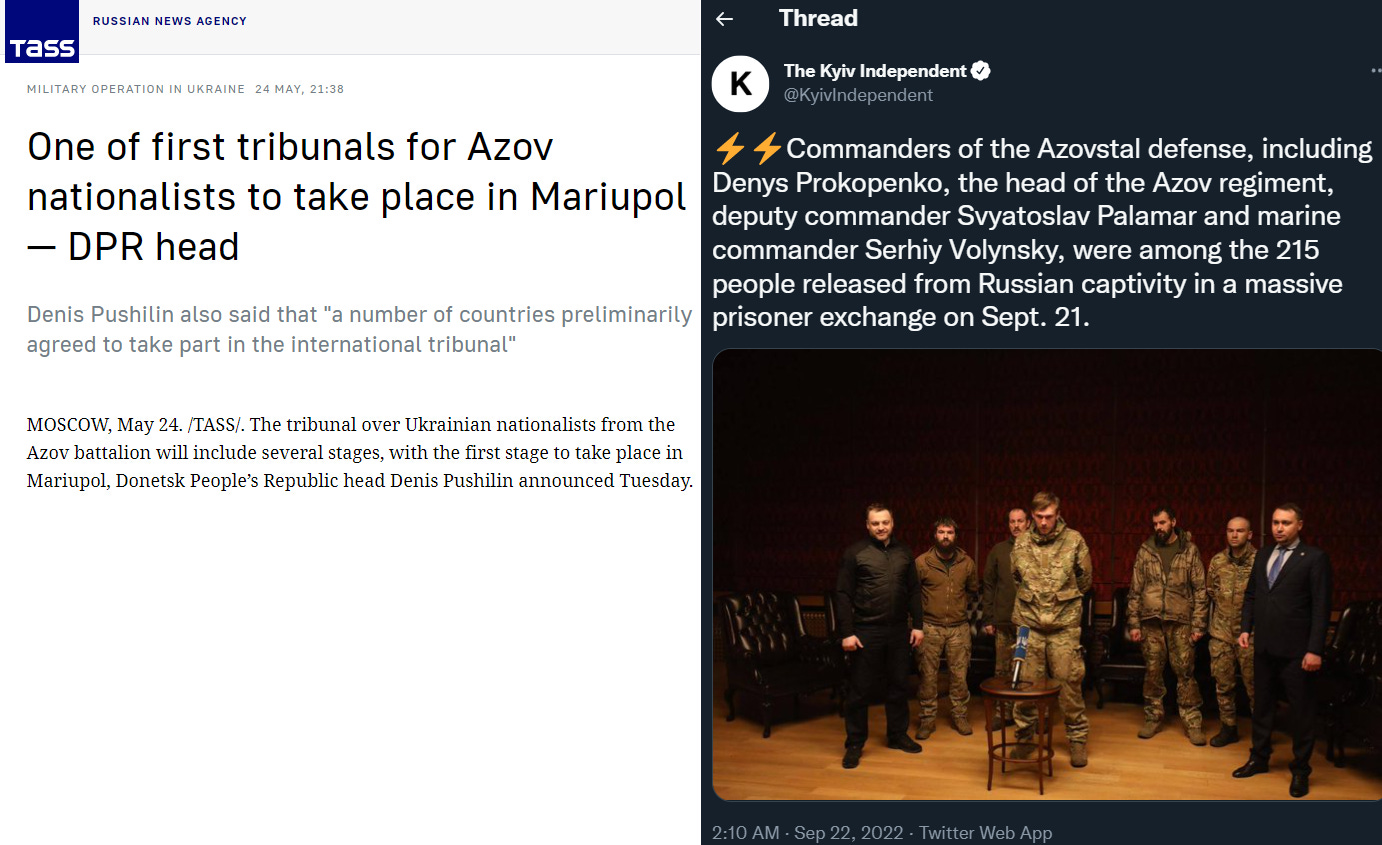

But there’s more. When Russia did manage to accomplish what we might call “a concrete example of denazification”—the Nazis were released.

I’m of course referring to the very controversial decision to exchange members of the infamous Azov battalion—including a senior commander—as part of a prisoner swap. The fact that oligarch/Putin friend Viktor Medvedchuk was included in this trade was not a good look.

Obviously, securing the safe release of Russian soldiers is important and praiseworthy. But the fact that these Azov guys were slated to be tried by a military tribunal for crimes against the people of Donbass, and yet somehow ended up on Roman Abramovich’s private jet, where they were fed tasty snacks, raises some uncomfortable questions.

Besides, if Putin was comfortable with putting Russian soldiers in harm’s way in order to bring these people to justice, why would you release them once they were captured? That doesn’t make sense to me.

I should add that if you followed Russian-language commentary about this strange episode, you would know that it was almost unanimously condemned.

By the way: One of the most high-profile “catches” from Mariupol—a Brit named Aiden Aislin, who was sentenced to death, but later released—recently revealed he was back in Ukraine.

Some have argued that Russia’s territorial gains in Donbass constitute “denazification”, and I’ll accept that as a valid point of view. However, I don’t see how anyone could claim this objective is anywhere close to being completed.

Objective status: Incomplete, and how to make progress is, at best, unclear, especially when Russia is comfortable trading neo-Nazis for oligarchs.

A few closing thoughts

In December 2018, four months after DPR leader Alexander Zakharchenko was assassinated, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov engaged in some rather lively geopolitical banter with a journalist from Komsomolskaya Pravda:

Lavrov: Do you propose to recognize the DPR and LPR?

Komsomolskaya Pravda (KP): Certainly.

Lavrov: And further?

KP: And then we defend our territory, which we recognized.

Lavrov: And you want to lose the rest of Ukraine, leave it to the Nazis?

KP: I believe that the Nazi regime must be fought!

Lavrov: We will not fight with Ukraine, I promise you this. Sometimes the recognition of independence, as you are now proposing, of the DPR and LPR and the declaration of war—I can’t imagine how it is, how will Russia go to war with Ukraine? Sometimes this is a manifestation of a nervous breakdown and weakness. If we want to keep Ukraine as a normal, sane, neutral country, we must make sure that everyone who lives in Ukraine is in a comfortable state.

Allow me to explain why I am sharing this exchange with you.

What’s done is done. And let’s assume Russia had pressing, time-sensitive reasons to launch the SMO in February 2022—reasons that did not exist in 2018.

Still, what Lavrov said—the thrust of his argument—remains true today. That is, by launching a military campaign against Kiev, Russia would risk “losing” whatever remained of Ukraine after the cessation of hostilities.

To me this actually sums up the entire conundrum for Moscow.

And, unfortunately for Russia, a very large portion of Ukraine is still firmly under the control of “the Nazis”, which means when this war ends—and it will have to end, eventually—there are going to be long-term consequences. The creation of a permanent “anti-Russia” on Russia’s border, for example.

War is a dirty business, and whether or not it is “justified” is secondary to whether or not it creates outcomes that are more advantageous than the pre-war reality.

Observing what has occurred over the past year (plus a few months), it seems that most (if not all) of the problems that existed pre-February 24 have not been corrected—in fact, almost all of these problems have become worse.

However, I want to stress, again, that I acknowledge there is no way to judge whether this conflict will lead to a better tomorrow—both for Russians and Ukrainians—for the simple reason that we don’t yet know how it will end.

But if that is your argument (“it’s too soon to say! You are being very irresponsible by saying the things you are saying!”), then you must also concede that it’s irresponsible to talk about Russia “winning”, because none of Putin’s objectives have been fulfilled, and in some aspects, the SMO has made it more difficult to achieve them.

I would also like to urge people not to assume, or insinuate, that anyone who questions Russia’s imminent “victory” has been blinded by subconscious bias.

In the closing minutes of his chat with Jesse, Brian brought up the fact that Mr. Zurawell was half-Ukrainian. I am not sure what he was trying to get at, but if he was inferring that only Ukrainians (or half-Ukrainians) have objections to the SMO, he is sorely mistaken. A great many Russians have expressed bafflement as to why this war was necessary, and have openly questioned what it is accomplishing.

I will provide a few examples.

There are regular discussions about the conflict at Yaplakal, one of Russia’s most popular internet forums. I would describe this message board as a hangout for “Russian normies”—a place for Average Ivans to vent and commiserate together. Politically, they are mostly centrists, but many of them have no illusions about the West—although the same can be said of their views about the Russian government.

On April 4, 2022, one user posted an article about Putin promising that the goals of the SMO would be fulfilled.

Here’s an excerpt from the most-upvoted comment:

Well, that is, Russia’s population will shrink by a thousand more young, healthy guys, and there will be even more widows, fatherless children, and grief-stricken parents. […]

Can anyone explain to me, after a month and a half of this meat grinder, what we’re doing there? For what did thousands of soldiers die or become disabled? […]

What were the goals, and what did they get in the end?

Almost a year later, on April 18, 2023, someone posted a message from the governor of the Murmansk region, announcing the deaths of six locals who had been fighting in Ukraine.

The top comment:

The young guys died for no reason in this fucking unnecessary war.

Well, you get the idea.

I will now get a bit “personal”. I have several friends living in various parts of Russia. One of them resides in Tatarstan, and is an officer in the reserves. I would describe his political beliefs, and overall demeanor, as quite conservative.

He reported to me that several of his colleagues at work were mobilized, and that one of them did not return. He thinks the war is senseless, and has no possibility of fixing the problems that existed pre-February 24. (He was overjoyed when Crimea reunited with the Russian Federation, by the way.)

My son is a Russian citizen, but he has relatives who live in a suburb of Kiev. When the SMO started, we would Zoom chat almost daily with them. We were all rather confused about what was going on, and together we expressed our hope that whatever was going on, it would end in the nearest future.

These Zoom calls ended about two months later. Our relatives no longer wanted to communicate with us.

What you have to appreciate is that this conflict doesn’t just represent Ukraine’s (possibly irreversible) divorce from the Russian World, but is also a form of family divorce, in the literal and figurative sense.

It is very tragic, and it fills me with great sadness, just typing these words.

In closing, I want to emphasize that I did not write this blog post (which took me way too long, and now I am physically and mentally exhausted; and probably this text is riddled with typos, which I am too tired to identify and correct) as a “dunk” on anyone, or to wag my finger at those who hold views different from my own. I am way past that (although I readily admit I’ve dabbled in that kind of punditry in the past, and for that I am very sorry).

No, that’s not the point of this blog post. I am simply pleading: Isn’t it time we had an open, sincere dialogue about outcomes? What would victory actually look like?

I hope we can start having these conversations, because I think they are very important.

I am terribly worried that, in the end, nobody will win (except for a handful of very, very rich, powerful, and nasty people). It’s happened many times before, and I see no reason why it can’t happen again.

Sincerely,

— Riley

If you found this blog post useful, I would REALLY appreciate you tossing me a few tasty rubles. My SUMMER OF BLOG LOVE SUB-SPECIAL continues, and you can support my work with a 12-month subscription for the low price of $38. Thank you, friends.

Ever since I read on your blog some weeks back that gas and oil still transits via Ukraine to Europe I have become totally disillusioned with this whole business. This is a jack-up like every war. I think, influential people, with or without Putin, are in cahoots with the UN & WEF to have a war in which hundreds of thousands (or millions) of people will be killed and maimed. At least two objectives achieved - depopulation and elimination of fighting age men who can oppose the agenda of the aforementioned organisations in that part of the world. It is also a major distraction for a major portion of the worlds people while agendas are implemented.

No one (aside from that handful) wins. For Russia, the best result (if even measurable) would be a degradation (or slowing) of the West's 'Destroy Russia' project (which uses Ukraine as an instrument). But then, what does that matter, given that Russia is willingly heading into the same 4IR/WHO/etc dystopian dustbin as every other country? We'll all be lucky if it does not go nuclear (as the depop lobby is arguably hoping or agitating for - the neocons seem openly cavalier about it).